Chan Reis raced offshore for 20 years from 1972 to 1992 and sailed in the Newport Bermuda Race nine times—three times on the elapsed time winner, George Coumantaros’ Boomerang. Chan, who lives with his wife Ann in Hampton Falls, N.H., says he “compressed a lifetime of sailing into two decades,” and is now content to cruise or race in coastal waters or do an occasional delivery.

Above, CCA member Chan Reis visits the new Boomerang in 1996 after retiring from the active race crew several years earlier.

Chan’s interest in sailing remains keen and he is still an active Cruising Club of America member. Last year, he volunteered for the Newport Bermuda Race Media Team to produce videos that would help others prepare for the upcoming 2020 race. Since early this year, his expanding series of videos have begun appearing at bermudarace.com and on the Bermuda Race YouTube channel based on interviews with members of the Bermuda Race Organizing Committee (BROC). The videos provide introductions to the race, safety training, yacht inspections, crew qualifications, and the current entry process. They also demonstrate the expertise and approachability of the sailors who volunteer as race organizers.

“Conventional wisdom some years back was that talking heads were boring,” Chan says. “One day I put the question to a friend of mine, Ralph Paskman, a sailor who had retired from CBS News: ‘How did a show like 60 Minutes turn that idea on its head?’ He told me the difference was that the show gets interesting talking heads on camera. I decided interviewing experts from the Bermuda Race Organizing Committee would be a good test of the theory in the sailing world.”

Back when he was racing, Chan had taken still cameras aboard, but his video interest came relatively recently, when he realized he had a good camera and production studio in his pocket—his iPhone 8. Like many smartphones, the camera’s image quality is excellent and the phone comes with iMovie, a free editing app.

Shooting an iPhone video

Chan’s shooting tips begin with encouragement to capture natural sound whenever possible. At the same time, you have to guard against wind noise, which he says is easy to generate across the iPhone’s integrated mic. “Be selective about shooting to make sure you can minimize or eliminate wind noise,” he says.

For interviews, Chan uses a tripod and a lavaliere microphone with Lightning connection when circumstances permit. Accessories for the iPhone include an adapter for attaching the phone to a standard tripod.

Using a small lavalier mic can make a big difference in sound quality, Chan says, although in an enclosed space such as a boat’s cabin, the camera mic can pick up two people in conversation well if you’re shooting from close by.

When conducting a formal interview, Chan uses a tripod that holds an iPhone, a lavalier mic, and whenever possible a natural, outdoor background with water views. When he has rushed an interview, he’s usually regretted the resulting wind noise, the background, or both. “I’ve learned that the extra time spent getting the background and positioning right is worth it,” he says.

Chan also recommends setting up close enough to the talking head that you can see head, shoulders and chest comfortably without using the camera’s zoom capability. The subject will be a little more than an arm’s length from the camera. He also points out that the iPhone handles varying light well and his rule of thumb is to examine the subject’s face and clothing through the viewfinder to make sure the subject is neither washed out nor in deep shadow.

“Your other enemy is too much movement,” Chan says. “When shooting, we have a tendency to want to move the camera, forgetting that in the final editing you can do some of that to help the images come alive. I think static shots are best, or slowly panning or tilting. It gives you more options at the end of the process.”

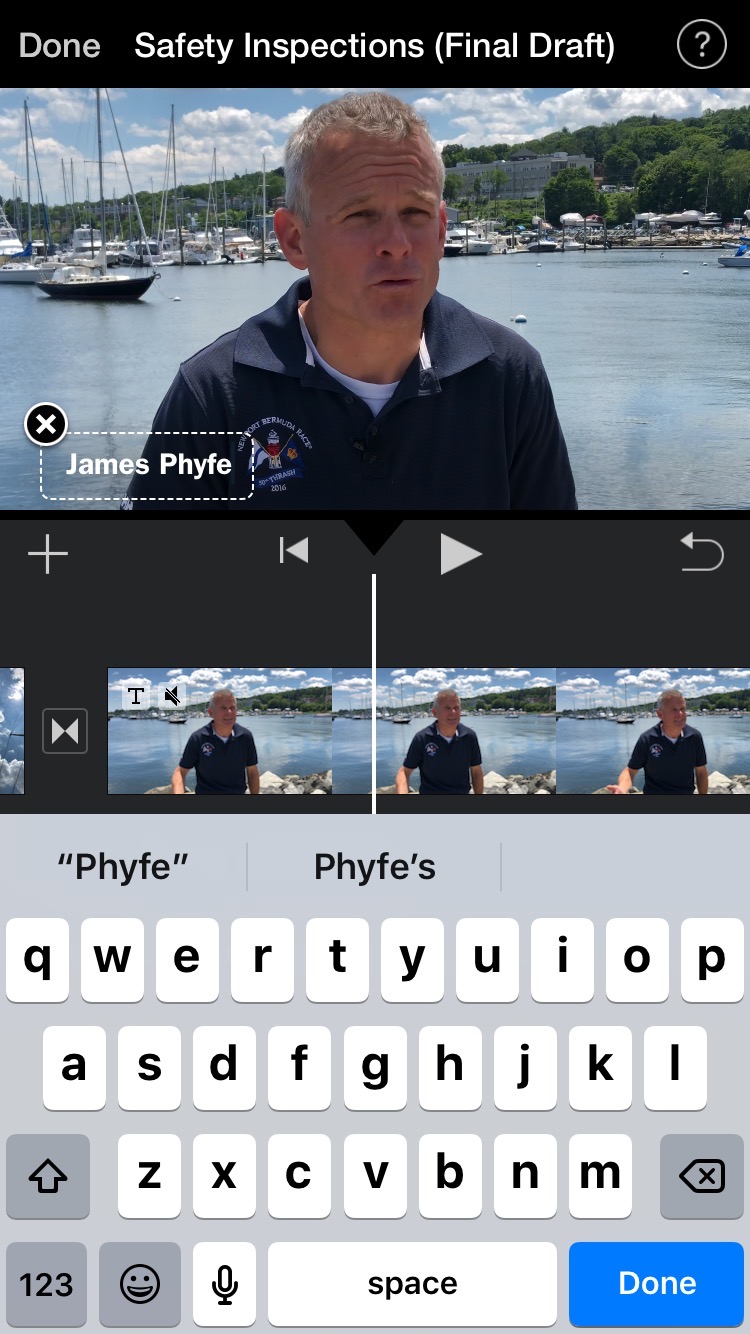

This iPhone screenshot shows the positioning of the talking head’s name in the lower left corner of the screen.

Editing on the iPhone

“The wisdom of the expert is the baseline of the narrative, or the A-roll,” Chan says. “I trim and cut this footage, editing out digressions and sometimes changing the order of the answers for a more cogent flow. Typically, I shoot an interview for up to 20 minutes, which gets distilled down to 2 or 3 minutes of finished video.”

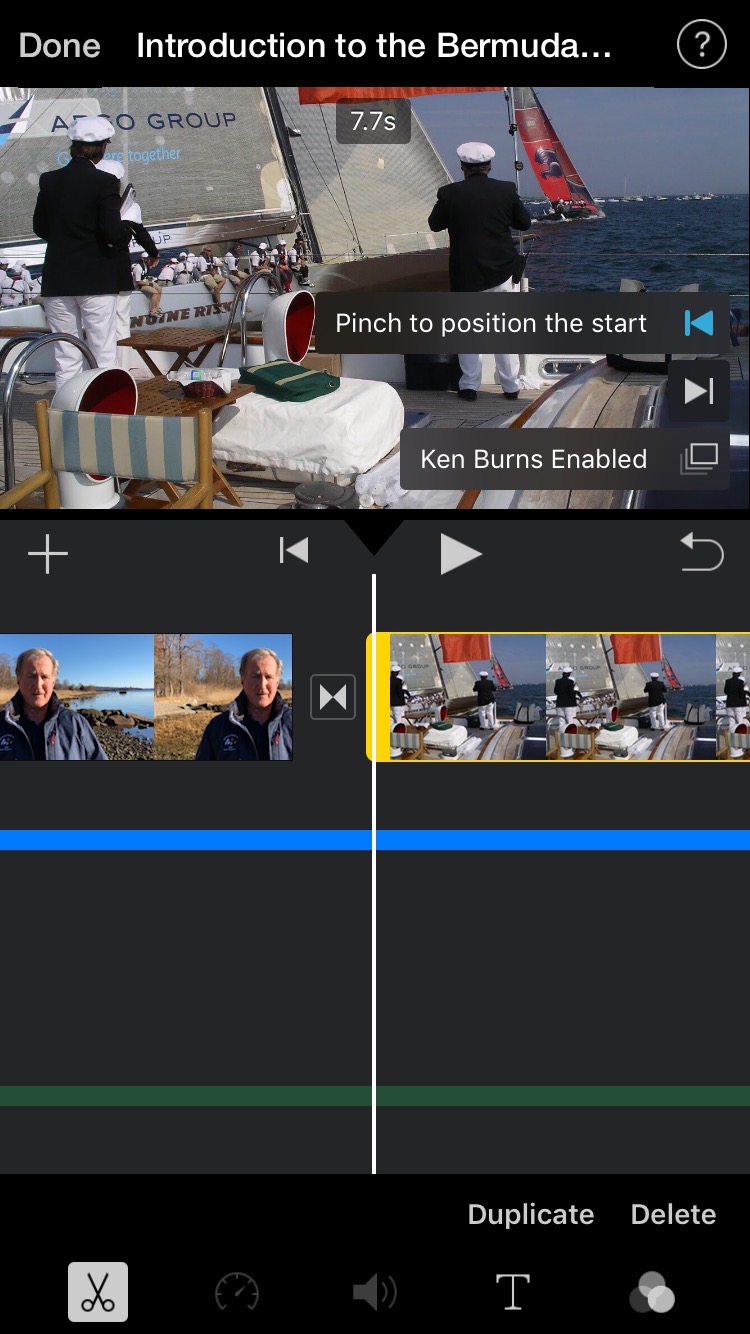

iMovie has a “Pinch to Zoom” feature that allows changing the field of view of the talking head from wide to tight.

To vary the visuals when the talking head is on screen, Chan sometimes uses iMovie’s Ken Burns Effect, which allows you to pinch and zoom, essentially cropping the video clip to make the camera appear to zoom in to or out of the clip. But he also cautions against over-using this editing tool.

Still photos can be dropped in from the photo roll on your phone. iMovie allows you to enable the “Ken Burns” setting, pinching the starting point and end point. The result is a slow pan, tilt or zoom of the image, a technique popularized by the well-known PBS documentarian.

The supplemental footage Chan uses is called the B-roll, which can either be video or stills that add depth to the video. He typically uses 3- to 7-second clips that he has shot himself, sourced from the media team’s library, or sourced elsewhere. The iPhone has a screen-record feature Chan sometimes uses for an online source, but he points out that you must obtain permission before using someone else’s clips and also be sure the resolution is adequate. (Check the screen-recording resolution available on your phone.)

“Don’t rush to add music,” Chan says. “Whenever possible use the natural sound of water on the hull or a winch clicking.” He agrees that some videos benefit from the energy in music, but says, “Many who shoot and post videos step on some of the more natural effects by always adding music to it. I think it’s like putting headphones on at the beach instead of listening to the sounds of the surf.”

Working with a producer

Even if you can shoot and edit the entire video on your phone, Chan recommends working with someone else to review your work as he did with others on the media team for the Newport Bermuda Race.

“The person shooting the video will forget things,” Chan says, “and the subject will too. A knowledgeable extra pair of eyes will point out what’s missing or confusing and often make good suggestions.”

Chan travels for his day job and says that one of the real values of iPhone editing is that he can work through a number of small refinements late in an edit whenever he has some down time, in the hotel, airport, or wherever. He can then simply send by text message a new low-resolution version of the video for his producer to review.

Chan’s tools are simple, and he likes it that way. “The key is to recognize the limitations of your tools and don’t go beyond that,” he says. “Let the tools work their magic.”