The Search for Sailboat Stability: Reflections on the Sydney-Hobart Race, 2004

“Safety Moments, presented at CCA Stations and Posts”

By Chuck Hawley, San Francisco Station

(The following story was written about 18 years ago, after the Sydney-Hobart race in 2004. The issues raised regarding keel failures on race boats, as well as some cruising boats, have continued to this day. World Sailing maintains a list of keel failures from 1983 to the present which includes 93 documented cases of keel failures resulting in 29 fatalities.)

In 2004, the Sydney-Hobart Yacht Race proved once again to be a gear-buster. Held in the Australian Summer, this annual race has had more than its share of heavy wind conditions, causing boats to abandon the race, lose their masts, occasionally sink, and on rare occasions, fatalities. The most recent heavy weather race was in 1998, which has become almost as famous as the Fastnet Race in 1979 as a test of boat construction, seamanship, and sailor’s bravery.

The 2004 race will probably be regarded as a “moderate” race compared to previous years, but it was memorable due to the failure that happened to one of the boats favored to finish first in the 628 mile race. Skandia, the winner of the 2003 race and a state of the art 30 meter (98 foot) sloop, was leading the race as conditions deteriorated on the first day. That’s when the crew discovered that the canting keel’s hydraulic cylinder was beginning to fail.

A note about recent sailboat designs and “canting” keels: Since sailors began to apply sail power to move a boat through the water, stability has been both desirable and challenging. A boat with too little stability simply rolls over when sail area is applied, unless sailing more or less downwind. The Polynesians discovered that you could put a second hull on the downwind side of a sailboat and create stability using buoyancy (and catamarans and trimarans have continued to be the fastest designs of all to this day.) In European ship design, more emphasis was put on creating stability using heavy weight in the bottom of the ship in the form of ballast or a lead or iron keel. As the ship began to heel, the keel swung away from the center of buoyancy of the vessel, and caused a force to be exerted which balanced the force of the sails.

The problem with using keels or ballast is that it is heavy, and heavy boats are generally slower compared lighter boats. In racing boat design, where every pound of unnecessary weight is seen as “the enemy”, designers began to concentrate the weight lower in the water by increasing the draft of the sailboat and by putting all of the weight in a mass at the very bottom. A famous French sailor, Eric Tabarly, went so far as to make a keel out of spent uranium due to its density compared to iron or lead. The trend towards small deep keels was apparent in the IACC or International America’s Cup Class boats, where 80%+ of their total weight is in a torpedo-shaped bulb about 12’ below the waterline. This trend has continued with boats like the former Volvo 70 Pyewacket with its 19’ draft.

Water ballast is the other technique used to increase stability: seawater is pumped into tanks lining the windward side of the boat to create temporary “rail weight” which increases the stability of the boat. What’s great about water ballast is that it can be easily dumped back into the ocean when not needed, thus resulting in a lightweight boat.

|

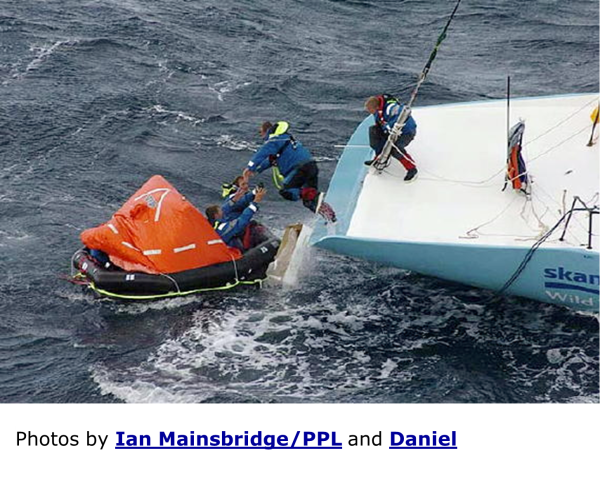

Photos by Ian Mainsbridge/PPL and Daniel Forster/Rolex |

OK, but what does this have to do with Skandia? Skandia, like many racing boats built in the last two decades, has a canting keel where the keel can be swung from side to side using large hydraulic cylinders. By swinging the keel to the upwind side, the keel is much more effective just as crewmembers are more effective when they sit on the weather rail and put their weight where it will do the most good. By increasing the righting moment of the keel, this allows the yacht designer to either use a smaller, lighter keel, or larger, more powerful sails. In either case, the boat sails faster.

However, it’s no small engineering feat to create a waterproof junction between the keel on the hull, and to create a hinge capable of withstanding all of the forces, and to create hydraulic cylinders with enough strength to hold the keel out to one side of the boat in rough conditions. It was exactly those hydraulic cylinders that failed when Skandia was approaching the coast of Tasmania on December 28, causing the keel to swing to the downwind side of the vessel and start flopping around.

|

Photos by Ian Mainsbridge/PPL and Daniel Forster/Rolex |

As the crew attempted to power Skandia towards the calmer waters along the shore of Tasmania, the keel began to rip the hull of the boat, and the decision was made to abandon the multi-million dollar boat to prevent injuries to the crew. As can be seen in the accompanying photograph, the crew jumped off the stern of the vessel into life rafts, where they were quickly rescued by the Tasmanian police. The keel later tore free from the bottom of the boat, whereupon it quickly capsized. At last word, (Jan 1), Skandia was being towed upside down towards Hobart.

According to the skipper, Grant Wharington, “We are effectively like test pilots rolling around in formula one racing cars, and I am still a bit baffled as to what actually happened.”

One outcome is likely: after each of the recent yacht races where there have been major failures of vessels, safety standards will be investigated and it’s likely that changes will be made. While these changes frequently affect the type of gear that boats must carry when going to sea, it’s likely that Skandia’s keel failure will impact the types of boats we go to sea in.

(As we discussed in a recent Safety Moment, in 2020 the Special Regulations subcommittee of World Sailing added requirement 3.02.2 to the “Special Regs” as well as Appendix L which describes a regular inspection process for the keels and rudders of boats racing in World Sailing events. It’s not known whether this inspection process might have prevented Skandia’s keel failure, but it seems like a step in the right direction.)

The Cruising Club of America is a collection of passionate, seriously accomplished, ocean sailors making adventurous use of the seas. All members have extensive offshore boat handling, seamanship, and command experience honed over many years. “School of Hard Rocks” stories, published by the CCA Safety and Seamanship Committee, are intended to advance seamanship and help skippers promote a Culture of Safety aboard their vessels