Medical Emergency at Sea

“From the CCA School of Hard Rocks

...lessons learned in pursuit of the Art of Seamanship”

By John Robinson

We were on the last leg of an Atlantic crossing - the first serious offshore experience for three 30 somethings. I was the skipper on my Valiant 40, HALCYON, with my two best friends from high school and the Air Force. We were seven days out from Terceira, Azores and three days from Falmouth, England on what had been an uneventful passage.

|

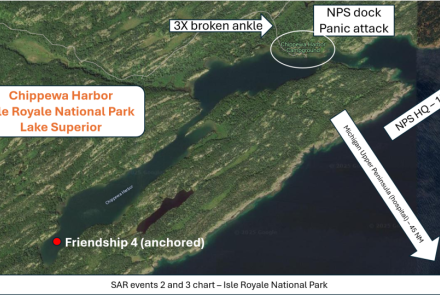

Position of HALCYON at the time of the medical emergency. |

When my relief at the midnight watch change didn’t appear, I went below to wake him up. He was curled up on the port settee. I called to him quietly first, then a gentle poke on the arm - no response. Then louder, harder - and I realized he was tightly curled, every muscle tense, eyes wide open, but still non-responsive. Tom was a diabetic.

I knew of his condition and had been briefed by the doctor and nurse who helped me with the planning for medical emergencies before we left. They supplied me with 50% and 5% Dextrose solution, syringes and an IV drip kit. Tom had the insulin. They also warned me that if Tom had a serious problem, as a layman I would not be able to diagnose whether he needed insulin or sugar. All I needed to know was that if he needed insulin and I gave him sugar, he would get worse; if he needed sugar and I gave him insulin, I would probably kill him.

Simple decision: get sugar into him. But, how? We had Coca Cola aboard, so I tried to pour some of that into his clenched mouth, but it just ran down the outside of his mouth. No reaction. A piece of Milky Way candy bar pushed into his mouth. Maybe a little bit of reaction, but not clear. Meanwhile, our other crew was on the VHF and SSB with MayDay calls, hoping to raise a nearby ship that might have a medical officer. Nothing. We hadn’t seen a ship in two days and were outside the major shipping lanes.

Time to get serious with the 50% Dextrose solution. Although I had never given an injection, I had received them and watched them given. If there was ever a time to try, this was it. I filled the syringe and enlisted the other crew in helping to pull Tom’s arm down from its clenched position so I could access a vein to inject. My first try raised a bubble just under the skin. An obvious miss. Second try, same result. After about 8 tries (and 8 bubbles) I was worried. It’s not working; now, what do I do? Fortunately, Tom didn’t seem to be worsening.

I realized that we had a plastic bottle in the galley cupboard filled with honey. Perhaps it would work if I pushed the nozzle into Tom’s mouth and gave it a good hard squeeze, forcing some of the honey in. It worked almost instantaneously. Tom’s body relaxed and, shaking his head like someone waking from a deep sleep, he looked at his arm, the bubbles, and me and asked “What the hell is going on…?”

So, what’s the lesson here? I’m pretty sure there are several, but one stands out above the rest for me. I had planned for the problem. I had provisioned for the problem. I knew what to do. But I had neglected the last step: I didn’t know how to do it. We were lucky.

The second lesson is that it’s essential to know the medical history of your offshore crew, especially medication dependencies, so that you can help prevent potential issues and deal with them if they arise.

The Cruising Club of America is a collection of passionate, seriously accomplished, ocean sailors making adventurous use of the seas. All members have extensive offshore boat handling, seamanship, and command experience honed over many years. “School of Hard Rocks” reports, published by the CCA Safety and Seamanship Committee, are intended to advance seamanship and help skippers promote a Culture of Safety aboard their vessels